Manipulating the velocity of money in proof-of-stake

The false dichotomy of ultrasound money deterring token usage.

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

A frequent topic of discussion is whether the Ethereum community, and by extension the monetary policy of the ecosystem, needs to do anything to encourage transactions after The Merge. One crowd speculates that the expected deflationary nature of the token supply will push the rate of saving (rather than using) tokens higher as owners anticipate a larger future market share.

There have been a number of high quality rebuttals, including a recent one by Domothy, focusing on the negative feedback loop: decreased usage leading to less burn which in turn incentivizes more usage, etc; but there is a elemental aspect to the dynamic that invalidates the entire discussion.

In proof-of-stake:

a lower issuance rate leads to less saving and more usage;

a higher issuance rate leads to more saving and less usage.

From a traditional monetary perspective the above claim seems delusional, but proof-of-stake inverts monetary dynamics.

Let’s walk through how issuance and inflation change the velocity of money in different financial systems.

Fiat Economy

In a fiat economy, the velocity of money generally correlates with inflation. The relationship is complex and is additionally dependent on changes in the money supply as well as the quantity of goods produced, but velocity and inflation largely move together.

A simple way to conceptualize the relationship is that during times of higher inflation, people see the future value of their money as lower, and therefore they are less likely to prioritize saving or to delay large purchases. In an infamous Bloomberg article, people living through hyperinflation in Argentina offered the following advice to Americans:

Spend Your Paycheck Right Away

In a high-inflation economy, money that sits in the bank is losing value. Each day, those $100 on deposit buy a little bit less. As a result, many Argentines spend their paychecks as soon as they receive them, carting away weeks worth of groceries in a single shopping trip, even if some of it -- excess meat, chicken, fish -- will sit in the freezer for months.

The causality goes both ways, so I’m not going to argue whether more spending causes higher inflation or whether higher inflation leads to more spending, but as a basic guide:

In a fiat economy:

a lower inflation rate correlates with less spending;

a higher inflation rate correlates with more spending.

Proof-of-Work

A modern proof-of-work system, like bitcoin, throws a wrench into the system by predefining an issuance schedule and preventing unplanned changes to the inflation rate. However, the underlying correlations remain exactly the same: if the inflation rate of a proof-of-work cryptoasset is higher, there is less incentive to save it—in theory leading to a more active supply. The result is that much like in a fiat economy:

In a proof-of-work system:

a lower inflation rate encourages less usage;

a higher inflation rate encourages more usage.

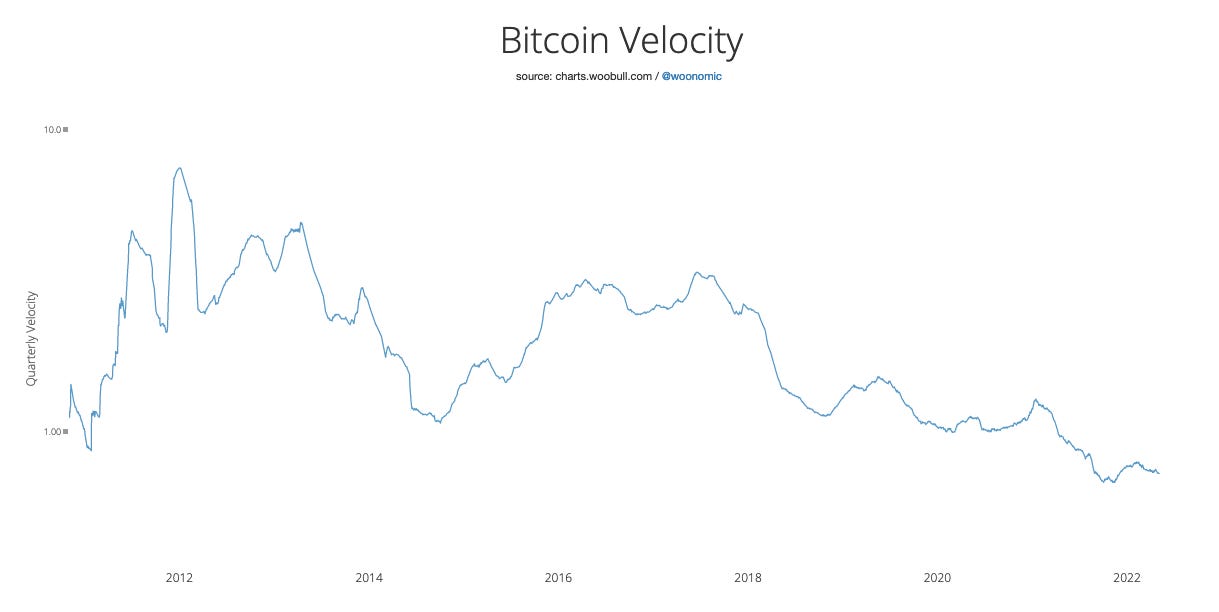

If we take a peek at the on-chain data for bitcoin, we see a long-term downtrend in velocity. Despite a large increase in the popularity of the cryptocurrency, its propensity to become a better store-of-value over time has led to decreasing relative transaction demand and more long-term saving.

If you want to incentivize transactions on a proof-of-work blockchain then you want to increase the issuance rate to disincentivize the absolute saving of coins.

This is one reason why I believe the monetary policy of bitcoin is ultimately flawed: as bitcoin gets closer and closer to its terminal issuance, its inflation rate decreases making it a better and better store-of-value. This disincentivizes the spending of the cryptoasset suggesting that the transition from mining subsidy to fee-only revenue will be a larger challenge than most expect. Certainly not an issue in the short-term, but does create a tail risk.

Proof-of-Stake

How does proof-of-stake flip this dynamic on its head? The point is subtle, but it comes through the non-Cantillon nature of the protocol.

In proof-of-stake, rather than inflation being an unavoidable side effect of issuance, it is a choice that every token holder makes. Debasement is the weight on one half of an imaginary scale; each person or entity must decide whether they value liquidity sufficiently to pay a small tax by sacrificing their share of the protocol’s issuance.

In order to encourage more on-chain activity, the key is to shift the weights on the metaphorical scale. To create more transaction demand the ecosystem must make staking less appealing and debasement less of an obstacle. The answer is to lower staking issuance, not to raise it.

In a proof-of-stake economy:

a lower issuance rate leads to more on-chain activity and less saving;

a higher issuance rate leads to less on-chain activity and more saving.

When you view staking issuance through the lens of a tax on holders who value liquidity, the point follows naturally: lowering the tax (to not stake) increases one’s desire to utilize the ecosystem.

Although many critics characterize high dApp usage and sound money as competing ideals, the two narratives actually support each other. Keeping issuance low is the key to ensuring the continued usage and development of a robust ecosystem of dApps on Ethereum and L2s.

- T.